Índice do artigo

PRIVATE EQUITY – FOUR VALUE LEVERS: Unlocking sustainable impact

Best-practice purchasing is now an even more potent source of value creation for private equity leaders.

When PE firms invest, they’re looking for ways to achieve immediate savings. The areas they look at, typically, are:

- Reduce costs through Procurement

- Technology consolidation and outsourcing of non-core functions

- Pricing optimization through margin strategies

- Complexity elimination through organizational and process alignment

Today, I’ll talk about all four.

THERE IS NO ROI IN PLANNING

Planning is a risk reduction tool, not a value creation one. To create value, you must have real commercial interactions in the market.

Market feedback better informs strategy than brainstorming sessions ever will, yet companies may pay millions for strategy consultants but not the same amount for limited product experiments.

A friend of mine has been a technology investor all his life. He has a passion seeing start-ups take ideas, turn them into minimum viable products (MVP), test them in real markets and pivot as needed for the next iteration of products and services.

Getting ideas out of the back-office and into the market quickly, as he would put it. He has guided such agile start-ups in industries ranging from software through fintech to telco equipment in both the US and China.

Whenever his companies “disrupt” incumbent competitors he admits to always being amazed that bigger rivals with better access to capital, talent, and channels are often incapable of mounting timely defenses in the market.

His observation is that there is a fundamental difference in how start-ups vs big companies perceive market strategy and more importantly how they spend their time when innovating.

Big companies spend 80% of their time planning and strategizing and 20% actually trying products in markets. Start-ups are the opposite, most of the effort is releases and pivots with real customers and products.

For example, Tencent in China is famous for such iterative approach by funding and incubating mobile startups, encouraging them to launch products early and often and keep pivoting the product, pricing, promotions until the adoption reaches a certain threshold, say 5 or 10 million active users.

If it does not, the product is shelved after a certain number of pivots. Early customers are actually funding later experiments and become customers for the future launches of similar products.

It becomes a virtuous cycle. He believes this mindset is followed in many larger Chinese companies which is the reason they are moving so much faster in AI, blockchain, automation, fintech and other areas than their European or US counterparts.

No such iterative value creation happens in planning, proofs of concepts, strategy retreats and similar endeavors devoid of real, commercial market feedback. Planning is useful to avoid risk and traps but should be limited to a small portion of innovation time and resources.

Build, ship, get feedback and adjust the approach until the customer’s need is met. That’s value creation and it has always been. There is no ROI on planning alone.

At least that’s what my friend convinced me of.

FOCUS AREA ONE: PROCUREMENT AND SUPPLY MANAGEMENT

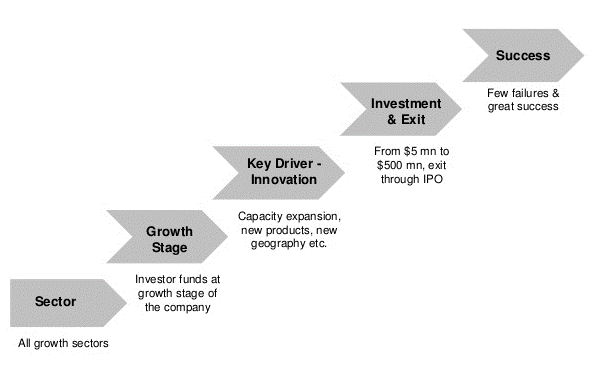

A careful review of purchasing is typically part of any private-equity (PE) playbook, with procurement savings factoring prominently into 100-day and longer-term business plans.

As part of the process, procurement professionals are typically charged with finding and acting on low-hanging opportunities like requesting price reductions and volume discounts from suppliers.

Leading PE firms are adopting a more comprehensive and transformative approach, powered by new digital and analytical tools, that can lift earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) by 20 percent within six months.

These tools, combined with the right approach and methodologies, enable rapid sizing and capturing of the opportunity, permanently changing the way investment and management teams look at procurement—and other aspects of operations.

Here I will describe the new approach, focusing specifically on the impact that digital tools, advanced analytics, and new methodologies have had on midsize-portfolio companies in a variety of industrial sectors.

Digital tools and advanced analytics

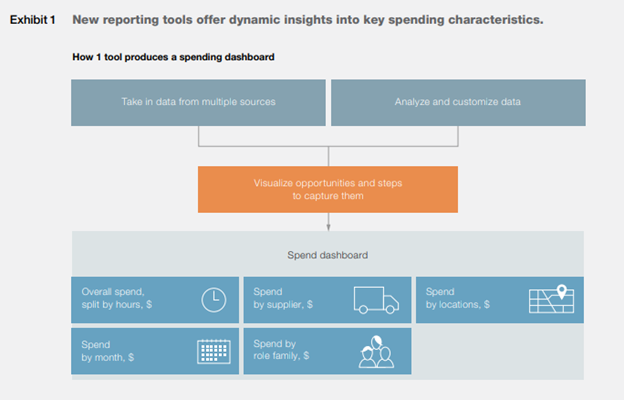

Pragmatic use of new digital and analytical tools can support a step change in supply-chain performance by enabling three key activities: creating transparency into procurable spend, identifying value potential, and supporting value capture.

Creating transparency through advanced spend intelligence

A common challenge for many midsize companies is knowing precisely on what and with whom they spend their money.

Fragmented and incomplete data and multiple, unconnected sources of information can make it challenging to determine a spend baseline, identify areas of opportunity, and track impact.

Many professionals believe that getting better data requires significant investment of time and money in new IT systems.

However, new digital solutions allow companies to make sense of dispersed, partial, and often incorrect spending data in just a few weeks.

They can patch together disparate software systems, extract data from both internal and external sources, cleanse them, and intelligently categorize them in sufficient detail to provide a “single source of truth” for external spend.

Procurement professionals can use this data set to perform a wide range of analytical exercises to identify areas of opportunity.

For example, they can look for pricing or specification discrepancies between different plants or divisions, excessive spend fragmentation, and disconnects between raw-material prices and commodity-market indexes—all are markers of opportunity that should be further investigated and transformed into cost-saving initiatives.

Exhibit 1 illustrates how a web-based tool can collate and clean data, and offer several useful analyses in each category of a company’s spending.

Identifying value potential

Knowledge and insights are power—a truism, of course, but in procurement, superior knowledge is vital. Insights into high-spend categories will help companies set the appropriate level of ambition (savings targets) and capture the full EBITDA potential.

In our experience, the traditional commercial levers, such as sending out requests for proposals (RFPs), negotiating with incumbents, developing new suppliers, and so on, capture less than half of the potential.

Claiming full value requires looking beyond price and into non-commercial levers, such as product design, raw-materials specifications, demand and usage management, and processes.

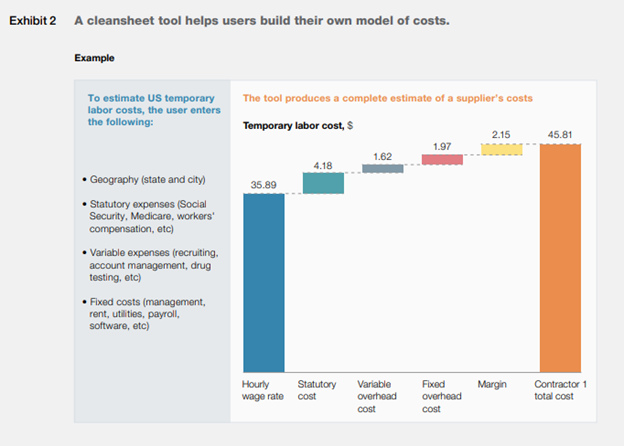

In doing so, procurement professionals can rely on a number of digital solutions to drastically simplify value identification and improve the accuracy of savings estimates.

New advanced-analytics tools used by midsize PE portfolio companies include the following:

- Online design-to-value tools, e-cleansheet solutions, and 3-D printers. Successfully deployed, these tools dramatically reduce the time and cost traditionally associated with design and specification changes. The insights generated have empowered procurement teams to negotiate on the basis of optimized product features. Typical impact is 15 to 30 percent of historical procurement costs. Exhibit 2 shows a simplified cleansheet analyzing temporary labor costs.

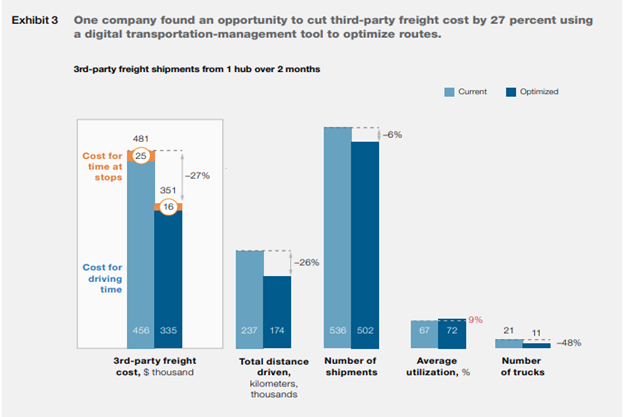

- Logistics and inventory-optimization tools. Companies with significant logistics and inventory costs such as freight and warehousing can optimize their footprint and logistic network, permanently reducing their internal and external logistic spend. Typical reduction in total logistics cost is 10 to 20 percent—and that is before renegotiating with suppliers on the basis of an optimized network. Exhibit 3 shows an example of how new tools can cut freight costs through shorter trips, increased utilization, and route optimization.

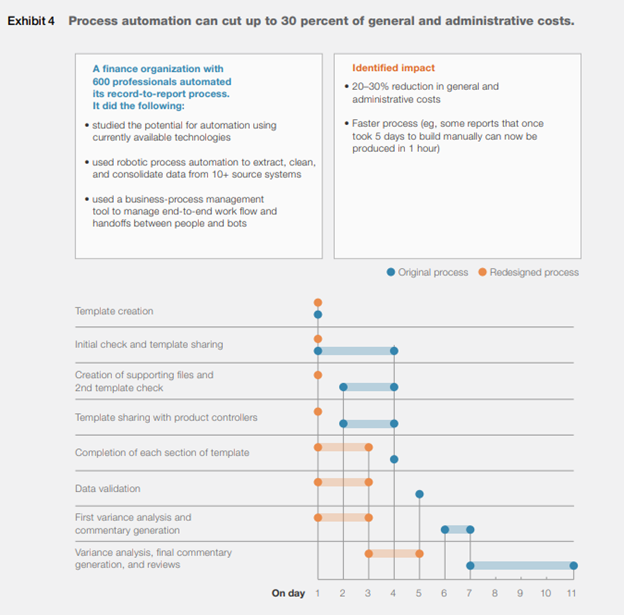

- Back-office process-automation tools. Companies with significant back-office spend (on both procured services and labor) can realize significant savings by automating and speeding up processes, typically 20 to 30 percent of general and administrative costs.

A robotic-process-automation system can extract, clean, and consolidate data from multiple source systems. Other tools then improve the management of end-to-end work flow and handoffs between people and bots, automating many processes and shortening cycle times.

Exhibit 4 shows an example of a reporting process in which most steps were automated, cutting overall time in half.

Supporting value capture with e-sourcing tools While not new, the latest electronic sourcing tools such as e-RFPs, e-catalogs, and e-auctions let purchasing teams reach more vendors and conduct more detailed, broader sourcing events in a fraction of the time of traditional RFPs.

If used pragmatically, these technologies let companies execute more sourcing events, with increased competition and transparency, compressing into days or weeks the work that would typically take procurement professionals years to execute.

Four elements of success

Leveraging digital tools is not enough to create step changes in financial performance. I advocate to pair new technologies with an approach based on four practices:

- setting ambitious targets

- mobilizing cross-functional teams including top management

- committing to total cost of ownership

- focusing relentlessly on execution Setting ambitious targets Once total savings potential is identified through advanced spend intelligence, it is easier to set an ambitious target.

Rather than just a target percentage or dollar amount—though those are important—PE investors should ensure that the actual procurement savings potential is reflected in the business plan of each portfolio company.

In our experience, after a quick diagnostic (two to three weeks), it is not unreasonable to expect a total procurement target of 10 to 20 percent of EBITDA.

High aspirations frequently lead to high achievement

A thoughtful stretch target can challenge an organization’s underlying mind-sets and assumptions.

It pushes the team to collaborate as never before and to develop novel ways of solving problems. CEOs, CFOs, and business-unit leaders should also visibly commit to the targets and pledge their time and energy to supporting the working team.

Mobilizing cross-functional teams including top management

Any initiative led and conducted solely by the procurement function is destined to underperform. It is crucial to pull high-level talent from across the organization to drive and support the effort.

Experts from finance, operations, sales, engineering, and manufacturing will bring broader expertise to the challenge at hand, allowing the team to see more issues and create better, faster solutions.

These teams are further empowered by clear definitions of roles, decision-making responsibilities, and a plan and venue to escalate issues that cannot be solved by the team. Committing to total cost of ownership More than half of all procurement savings potential typically comes from non-commercial levers.

As such, any value-capture effort that has the objective of capturing the full potential opportunity has to be centered on the idea of total cost of ownership. New digital and advanced-analytics tools can make it easier and faster to look beyond price to identify opportunities in design, specification, usage, and process.

Focusing relentlessly on execution Progress on initiatives should be reported to executives at least biweekly to drive momentum and urgency, and to ensure timely decision making.

Promising initiatives frequently die on the vine because “we’ve never done that before” or “we know the business will say no.”

Engaging frequently with the appropriate stakeholders sustains the momentum necessary to drive change through the organization. It’s important to note that initiatives don’t happen all at once, or at the same pace.

To engage the organization in the process, companies should establish stage gates to assign initiative owners, validate potential savings, and then quickly plan and resource them through execution.

Successful teams frequently set up war rooms where they can track initiatives visually. They identify obstacles to completion, resolve them when they can, and escalate them when they can’t through frequent periodic updates with top management.

In an increasingly competitive investing and operating environment, driving outsize performance in procurement can be the difference between exceeding investment targets and falling short.

A successful procurement transformation can increase run-rate EBITDA by up to 20 percent and make an even larger impact on enterprise value.

Furthermore, substantial and near-immediate improvement in cash flow can enable greater financial flexibility and investment elsewhere.

FOCUS AREA TWO: INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

The usual levers are well understood, mostly:

- optimize application portfolios

- consolidate network operations

- outsource non-business critical functions

- automate routine processes with RPA

Robotic process automation (RPA) also called Digital Workforce (DWF) software takes the mundane repetitive tasks and automates them to free up human workforce for more fulfilling jobs.

Increasingly the types of tasks move beyond data entry and reconciliation to more cognitive tasks like process analysis, reporting, and even basic decision making that fit predefine tolerance levels.

In the process, some companies reassign part of their human workers and establish a digital workforce. Imagine telling your digital assistant, “Alexa, please close the books, analyze overdue customers and initiate collections, prepare the report package for the board of directors, we’re at capacity so decide which customer order to delay”.

The most advanced automation happens in industries with experience in shared services, outsourcing and offshoring as that required them to displace and replace workforces and document processes well.

The digital workforce leaders are in healthcare, telcos, financials and professional services and even manufacturing and the traditionally IT-savvy tech industry is a laggard in comparison.

Many private equity firms have focused on digital initiatives for a while with bankable results in areas like omnichannel commerce, online auctions, predictive analytics in sales and operations.

Some of those digital initiatives took years to mature and often the ultimate gains in enterprise value ended up benefiting the next owners.

Broad digital transformation is better suited in certain investment styles (growth equity) and does not have the short term benefits needed for others (turnaround, carveouts) or later in the investment cycle.

What is attractive about digital workforce or software based automation, is that projects are done in 3-4 months and EBITDA gains accrue in 9-12 months.

This allows more flexibility in various investment styles and theses to incorporate automation as part of the main thesis elements or a side-car to the thesis (more on this below).

Working with firms with various approaches we have seen the following best practices:

- Establish digital workforce targets in due diligence then roll those targets to specific automation projects in the 100-day plan

- Use RPA as value accelerator for broader process optimization. While streamlining revenue lifecycle management in a healthcare portfolio company which will take years, you can partially fund the project with RPA-based savings by automating manual processes like claims entry, insurance coding, collections, etc. Some firms call it a side-car to an operating improvement element in the core thesis.

- Use RPA to generate PE-holding specific reporting requirements in the portfolio company like 13-week cash flow or debt reporting. There can be a digital worker (RPA bot) deployed to every new acquisition and start preparing board packages and reports. There is no need to change their ERP system or create massive manual processes in Excel

- Use bots to gather operational data not provided in underlying systems. This is especially true for a portfolio transitioning to Lean/Six Sigma. The cost of upgrading underlying ERP and MES systems could be cost-prohibitive. The bots can do data collection and analytics work.

- In a carveout or rollup, the new entity has to consolidate data from endless systems. Bots can accelerate data migration, data consolidation and even move data between systems. This can delay the need for a major IT consolidation project especially in later years of the holding period. The payback on IT consolidation tends to point outside the holding period.

- Containing SG&A growth in both growth equity and carveout is also an issue. Inefficient processes force back-office cost growth in line or above the top-line growth of the business eroding EBITDA gains. Deploying bots for new backoffice (finance, admin, HR, procurement) jobs can curtail the cost growth.

- Job requisitions – go digital first. Another lean digital workforce practice is to go digital workforce first for new job requirements. Do you need an analyst? It can be a bot. Do you need an accountant? Can probably be a bot. Research shows 40-60% job tasks can be automated. It is a lot easier to automate jobs that have not been filled yet, than to reassign existing staff.

Automation is a rapidly evolving field with PE portfolios demonstrating major impact on EBITDA gains and enterprise value. As the industry matures, benchmarking will evolve to set realistic targets and comparables to better inform PE teams and their investment theses.

FOCUS AREA THREE: OPERATIONAL COMPLEXITY

Adhering to four key principles can help companies increase the odds that their collaborations will create more value over their life cycles.

Downturns and acquisitions reveal a company’s weaknesses. An organization that seemed nimble and focused during a period of expansion may be sluggish and ineffectual when faced with declining demand.

Its very survival may depend on determining which products are making money, what customers really value, and which organizational bottlenecks are getting in the way of effective action.

One major cause for this sluggishness, in my experience, is complexity—product complexity, organizational complexity, and process complexity. In good times, all three are likely to increase.

The costs of complexity are usually hidden, so executives are often unaware of the magnitude of the problem. When the downturn hits, they may be unsure how to tackle it.

They often fail to identify the short-term actions that can reduce costs and create flexibility so the company can adjust to the new market conditions.

They may also neglect the longer-term steps necessary to balance complexity reduction with innovation as the company pulls out of the downturn and begins to grow again.

Managing complexity brings significant benefits in a relatively short time. One of the world’s largest natural-resources companies, for example, began its corporate life with only a handful of operations in just a few countries.

But as the company grew into a worldwide enterprise, its complexity grew even faster. Costs spiraled out of control, safety procedures were sometimes ignored and the company’s financial performance suffered.

A diagnostic assessment revealed huge opportunities for improvement from complexity reduction.

The company found that it had no fewer than 483 process improvement projects in the works—and that only 25 would deliver a significant impact.

Acting on these and similar findings, the company was able to boost operating income by more than 20 percent.

The “zero-base” approach to complexity

The challenge with managing complexity, of course, is that some complexity is necessary and advantageous, even in a downturn.

For example, country or regional business units are closer to the ground than headquarters and are more likely to know what customers want.

It takes a complex organization to provide enough local autonomy so products or services can be tailored to those customers while still taking advantage of global scale.

But that kind of complexity can be vital to sustain sales through a recession. A similar challenge arises when companies struggle to balance complexity and innovation.

Adding new products, services, features, and options creates complexity of all sorts. But companies become leaders by offering customers new choices, and in a downturn innovation may be a company’s salvation. (Consider where Apple would be today without iTunes and the iPhone.)

The key is not to eliminate complexity but to balance its benefits with its costs.

A useful way of analyzing the level of complexity in your—and separating complexity that’s beneficial from complexity that hurts the business—is to begin from a base of zero.

Imagine, for example, that your company produced just one product or service with no options or varieties, sort of like Henry Ford’s classic Model T.

A manufacturer with only one product would still need a supply chain, a factory, a distribution network, and a sales-and-marketing function. But it could greatly simplify its IT systems, its distribution and sales efforts, and its forecasting.

One plant manager with whom we discussed this exercise was bringing in 15 planes’ worth of parts almost every day just to be sure he could meet the next day’s production schedule. In a Model T environment, he noted, “All those costs would disappear instantaneously.”

The point of the exercise, of course, isn’t to go back to the days of the Model T—which, after all, succumbed to the greater variety offered by General Motors. The point is to determine your zero-complexity costs, and then assess the costs of adding variety back in.

In a tractor plant, for example, you wouldn’t need a scheduling system for one or two models, but you probably would for four.

Often the cost curve has just this kind of “knee”—a step change triggered by adding one more model or level of variety—and you can determine whether moving beyond the knee is worth the additional expense.

You can also assess the benefits of innovation, and determine the focal point where a given innovation overshoots what most customers want and are willing to pay for.

The key task—more essential than ever in a downturn—is to manage these balance points, keeping costs low while maintaining the level of variety and innovation that customers value.

For example, you might decide to eliminate individual options, and instead offer customers a small number of configurations that include the most popular features.

Thus Honda’s CRV comes in just eight configurations and thirteen interior/exterior color combinations, for a total of 104 possible build combinations, with no other options available. This is far fewer choices than most cars offer, yet the CRV is the hottest-selling vehicle in its class.

Similar kinds of analyses can diagnose organizational and process complexity.

We’ve found that companies get the best results by attacking product complexity first and organizational complexity next, and only then focusing on process complexity.

The reason is this: complex processes often reflect unnecessary product variety or poor organizational design.

If you attempt to simplify a process without changing product or organizational complexity, you find even more complexity cropping up in some other process area.

It’s like trying to make a balloon smaller by squeezing one part of it—another part just gets bigger.

Let’s take a closer look at each of the three areas.

Product complexity

Unnecessary product complexity means offering products, services, or options that relatively few customers want.

Most companies, of course, like to give their customers choices. But managers often overestimate buyers’ wants and willingness to pay for all those choices.

Sometimes, indeed, it’s obvious that companies have carried innovation too far. In 2006, Nestlé introduced a wide array of new variations on its basic KitKat candy bar in the United Kingdom, including passion fruit and mango flavors.

But the introduction of so many varieties had exactly the opposite effect from what the company hoped: Customers were turned off, and sales dropped 18 percent in the course of the year.

A diagnosis of unnecessary product complexity often turns up room for rapid improvement.

A major US industrial company, for example, was in its own acute downturn a few years ago: Competitive pressures had slashed its operating profits by more than half in less than six months.

Analyzing its SKUs, the company found that 80 percent of SKUs contributed only 20 percent of revenues. Needing quick results, it took a three-pronged approach to reducing this complexity:

“Drain the swamp.” The company evaluated each SKU through three lenses—customers, operations, and products.

Which were most important to major customer segments? Which fit best into the company’s operations and product lists? When it dropped an SKU, the company armed its salesforce with alternative products to offer major customers as replace ments.

These actions enabled it to reduce SKUs by 20 percent immediately—and it ended up adding back only two out of the 500 that it had eliminated.

“Make the best of what’s left.” The company then actively attacked complexity in its remaining product portfolio.

Within days it established higher order minimums, longer lead times, and larger production runs. Another quick hit: out sourcing low-volume product families.

Over time the company reassessed other make vs. buy decisions and established different service levels by customer and product group.

“Fix the shop floor.” With a less complex product line, the company set about streamlining its operations.

For example, it reduced the number of low-volume products running on high-volume equipment. It cut back on products with inherently high scrap rates or inherently short lead times, and products that required specialty materials or processes.

It also began altering design specifications so it could make more individual products on the same platform.

These complexity reduction efforts boosted operating profits by about two percent of sales—and about 75 percent of that improvement was achieved in the first year.

Even more important, they helped create a nimbler organization, one that could respond rapidly to changes in the marketplace.

Organizational complexity

As a company expands its product variety or moves into new markets, managers are likely to add organizational complexity.

For example, they may try both to maximize scale and to stay close to the customer. Pursuing both these objectives often leads to complex matrix structures, duplicated costs at different levels, and a lack of clear accountabilities.

Each decision to add an organizational layer may make sense, but few companies in good times assess the overall impact of these decisions on organizational complexity.

In a downturn, however, the performance burden of an overly complex organization becomes a major disadvantage.

We have found three specific areas that provide a quick payoff in terms of nimbleness and the ability to focus.

Increase spans and remove layers.

Unnecessary hierarchy contributes to a number of ills, including excessive head count, inflexibility, slower decisions, and a lack of accountability.

“De-layering” can help address all these issues. Companies typically begin by determining the average span of control (the number of employees assigned to any one manager) and the number of layers between the CEO and front-line employees (or between the head of a function and the lowest-level person in the group). They then compare those figures to the competition.

A US pharmaceuticals company, for example, found that competitors on average had 4.2 individuals reporting to each manager in their research function and six layers overall between front-line employees and the CEO.

Its own organization, by contrast, had only two research employees per supervisor and an average of eight layers from top to bottom.

Just getting its organizational structure in line with the competition allowed the company to save as much as $500 million a year.

Eliminate decision complexity

Decision paralysis is another pitfall of complex organizations. We’ll address this point in greater detail in a subsequent installment on strengthening the organization in a downturn.

In brief, however, many companies suffer from unclear decision roles and processes. This is bad in any economic climate, but can be particularly damaging in a downturn.

A tool we call RAPID—for Recommend, Agree, Perform, Input and Decide—can help cut through the mess. Take the case of UK department store John Lewis. Managers there realized that their product line was too complex—for example, they stocked nearly 50 SKUs of salt and pepper mills, while most competitors stocked around 20.

When they tried a new, leaner range of options, however, sales declined. The trouble was this: buyers had expected to maintain the same amount of shelf space.

But merchandisers, who put the products on the shelves, had reduced shelf space along with the number of SKUs.

By clarifying decision roles between the two groups—who was responsible for making recommendations, for offering input, for signing off on the recommendation, and ultimately for making and implementing the decision—the store was able to maintain the original shelf space with the new range of products. Sales climbed well above original levels.

Establish accountability for orphaned costs.

In complex organizations, it may be unclear who is responsible for any given operation, and scrutiny may often be lax.

This leads to “orphaned costs”: routine costs that are unaccounted for and unmanaged.

The magnitude of these costs can be startling. At the natural resources company we mentioned earlier, investigation determined that there was little or no accountability for approximately 40 percent of the company’s overhead costs.

Simplifying the organization helped the company attack this problem. For instance, it eliminated redundant finance organizations operations and clarified the responsibilities of those that remained, ensuring that accountabilities for every cost line were clear.

Each of these measures has its own payoff; together they help create an efficient organization that can move swiftly and focus on the most important activities rather than spinning its wheels.

Process complexity

Companies that do attempt to manage complexity usually begin with processes, often through efforts such as Lean Six Sigma.

Typically the emphasis is on how companies can execute all their current operations faster and with fewer resources.

But that’s the wrong place to start. The natural-resources company, remember, had 483 separate process-improvement projects in place.

But the whole collection didn’t add up to much, because the company had not yet attacked product and organizational complexity. Reducing process complexity should be a company’s last step, not its first. Here’s where to begin:

Look for the process improvements that add the most value.

Some processes are obviously critical in any business. A retailer having trouble getting the right mix of products on its shelves, for example, needs to address merchandising right away. In a downturn, the decision about which processes to tackle should be governed in part by how long it will take to yield results.

Fixing an inefficient product development process might take years, whereas fixing a poor inventory management process might take only a few weeks.

Companies can then focus on process improvements that promise the biggest returns. The natural-resources company found that 110 of its 483 process improvement projects were redundant or unjustifiable. Among the remaining 373, it identified 90 that had significant merit.

Management then evaluated each of those and narrowed the group down to the 25 initiatives that were likely to generate the most value. These are now closely tracked by a project management office.

Cut through the data clutter.

The natural resources company also looked into the information and metrics it used to manage the business, and discovered that people were drowning in data they weren’t using.

By determining what kind of management information it truly needed to run its business, the company found it could reduce its volume of reports by 40 percent in one major business unit.

That not only accelerated the decision-making process, it also liberated employees to focus on the activities that matter most to the business and saved $10 million. In cutting through the clutter, you may discover both too much data and a lack of consistency from one dataset to another.

At a telecommunications company, key metrics like the number of fixed-line customers differed depending on the data source used. And each silo within the business used a different set of data, one that supported its own view of the world.

The new CEO at this company had to find out which of the sources of data most closely reflected the truth and determine which methodolgies should be used for calculating key performance indicators.

That, of course, is the ultimate reward of complexity management. Companies can focus only on the products that are most important to their customers, saving the costs of unwanted production and boosting the margins of the best sellers.

By streamlining their organizations they make better, faster decisions, exert tighter control on costs, and can quickly reduce unnecessary headcount.

Managing process complexity helps companies see where they are overspending and allows them to track performance more effectively.

All these complexity management efforts help a company become lean and flexible enough to adjust to the changing market conditions in a downturn.

It pays off again when the economy improves and a company has stripped out enough complexity to accelerate quickly out of the downturn.

FOCUS AREA FOUR: PRICING – ANOTHER VCALUE LEVER OF PRIVATE EQUITY

Over the years, private equity (PE) firms have mastered the art of creating value for their portfolio companies through cost reduction, talent upgrades, and financial engineering.

Moreover, they have built valuable experience in recognizing patterns that allow them to spot and invest in the best portfolio targets.

In contrast, most PE owners do not display the same level of fluency or confidence in commercial productivity—especially in pricing.

In our experience, commercial improvements— such as those in a company’s pricing, customer and product mix, or sales volume growth—can create tremendous value for both the portfolio company and the PE owner.

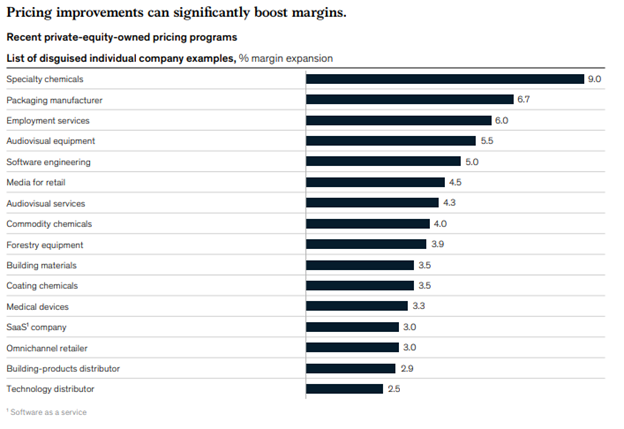

Specifically, when PE firms tackle pricing in their portfolio companies, we typically see margin expansion of between 3 and 7 percent within one year.

Factoring in potential pricing improvements can allow PE firms to be more confident in potential upside and differentiate themselves in competitive deals.

The direct and rapid margin expansion from pricing transformation creates more value for portfolio companies and investors alike during the holding period.

And highlighting a track record of both successful pricing improvements and additional pricing opportunities can result in a higher exit valuation.

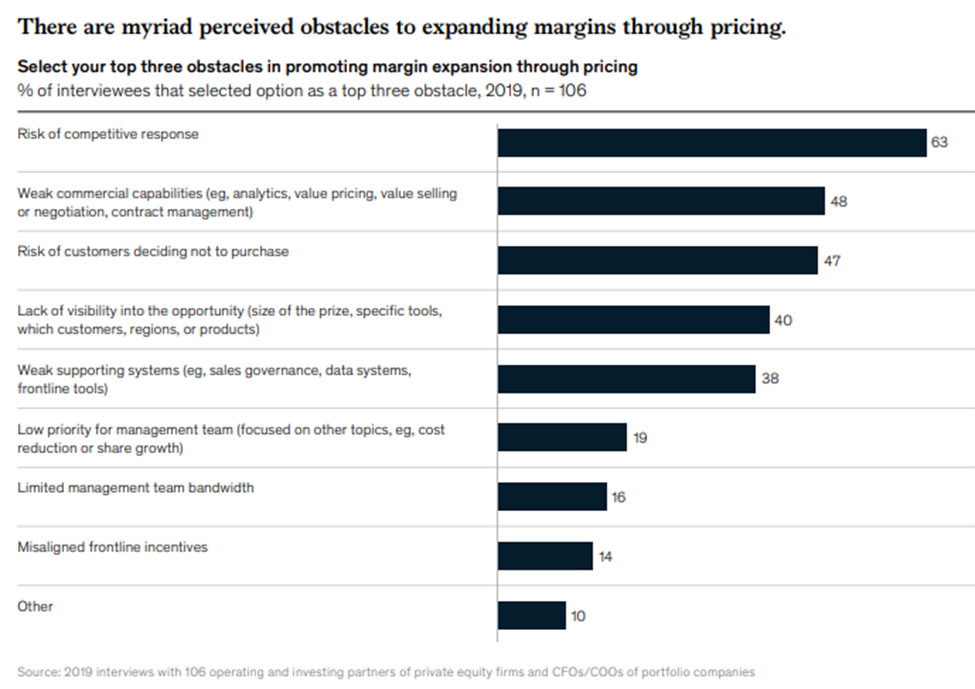

To better understand the barriers that prevent deal and operating partners from using pricing to boost earnings, we recently surveyed senior leaders from PE firms and their portfolio companies across Europe and the United States.

The findings suggest that while respondents view pricing capabilities as highly valuable, they do not effectively build and use those capabilities to design and implement pricing programs.

I also found that PE firms can maximize value by addressing pricing early, but value can be derived at almost any point in the deal cycle, from pre-deal diligence to the eventual exit.

Understanding PE’s approach to pricing

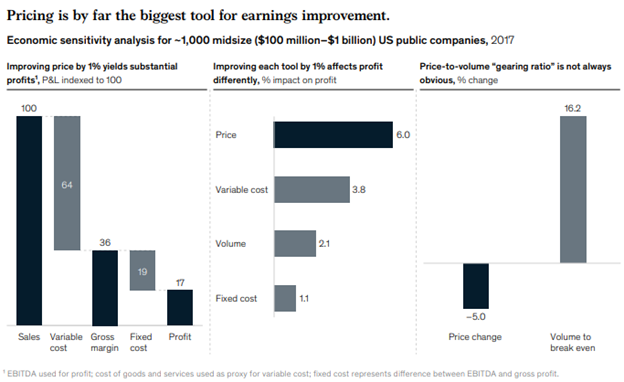

For a typical midsize US company, a 1.0 percent improvement in pricing raises profits by 6.0 percent, on average.

By comparison, a 1.0 percent reduction in variable costs and fixed costs yielded an increase in profits of 3.8 and 1.1 percent, respectively.

In practice, a midsize company acquiring a business approximately 30 percent of its own size with a similar P&L structure would have the same impact on its bottom line as a 5 percent improvement in margin.

Another reason that pricing is an attractive way for PE firms to create value is that any improvement flows almost entirely to the bottom line, net of any volume changes or investments made in tools and resources.

Pricing has an outsize impact on valuations given the EBITDA multiple view that investors apply, and in many cases, it can also lead to increased multiples and therefore further competitive differentiation.

To create value in their portfolio companies, PE firms and operators often start by gaining efficiencies through cost control, which has a lower perceived risk.

PE leaders cite multiple reasons for traditionally putting less emphasis on pricing to create value. Notably, the top concerns are competitive responses—that is, competitors would change their pricing behavior to capture more of the market—and customer defections.

From experience, we know that when pricing improvements are implemented in the right pockets of opportunity, the risk of customer loss is widely overestimated and investments in pricing capabilities typically have a high and quick return.

Even among deal and operating partners who broadly believe in the opportunity and view pricing as a key promoter of earnings, many underestimate its potential impact.

Thus, their investments in pricing opportunities continue to be low compared with procurement and other cost-saving measures.

Given that, it is not surprising that most management teams feel their organizations are underprepared and lack the resources to capture the pricing opportunity

How to create pricing value throughout a deal life cycle Firms can maximize value by addressing pricing early, but value can be derived at almost any point in the deal cycle.

More sophisticated PE firms and portfolio companies maximize value creation from pricing by focusing on different tactics throughout the deal cycle—before the deal, early in the holding period, mid-tenure, and pre-exit.

Before the deal: Sizing the opportunity

The first step is to assess the potential opportunity from pricing and build it into the upside case in a way that inspires confidence that value can be captured.

Firms often have less-than-ideal data and compressed timelines, however, to assess potential opportunities.

To formulate a robust perspective, experts need to hunt for patterns showing indicators that might help estimate potential value.

Although these predictive indicators vary by industry, combining them with whatever limited data are available in the diligence stage and insights from management reports and interviews can help differentiate an investment case and allow investors to bid more accurately and competitively.

For those opportunities where a pricing program is likely to succeed, we typically see a 3 to 7 percent margin improvement for PE portfolio companies.

Early in hold period: Creating a 100-day plan

Experience suggests that even though pricing improvements pay off, a company is more likely to invest adequate time and resources if the 100-day plan explicitly identifies pricing as a high-priority initiative.

To weave a pricing-improvement journey into a 100-day plan, PE firms across industries should focus on getting a few important things right: — A perspective on industry-pricing dynamics and structural-pricing headroom.

This information can be quite important for midsize players, particularly midsize companies that often operate in a niche part of an industry. — A definition of business and commercial objectives.

This includes size of expected impact from organic versus inorganic growth and volume versus price targets on the organic growth portions of the business. — An assessment of how price is set today for all products and customers.

Typically I find either legacy price points that have not been updated at a regular cadence or a lack of consistent methodology for setting prices in various parts of the organization.

- A clear and detailed picture of surcharges, rebates, and discounts. There should be guidelines for the whole organization around to what degree, by whom, when, and for which customer segments these terms and conditions are to be applied.

- An understanding of what elements of cost to serve are included in the price versus charged separately to the customer. These can include, for example, freight, rush orders, small-order surcharges, and raw-material cost changes.

- An analysis of pricing tools and processes in place. This assessment should also include gaps in the pricing feedback loop between marketing, sales, finance, IT, and customer service. In addition to these six goals, PE firms should work to align the management team’s incentives with pricing value-creation potential.

This alignment helps encourage ownership of the business among team members, as well as behavior that supports the company’s overall financial growth.

Mid-tenure: Solution design and mid-tenure tune-ups

For portfolio companies in their holding period, pricing can often be the right catalyst to spark margin and top-line growth.

In these situations, after a four- to six-week phase to identify potential opportunities, management typically prioritizes a handful of pricing tools likely to generate the most value and explores how to capture that value sustainably.

If the company at least started the process of developing a pricing road map as part of the 100-day plan, then midtenure becomes much easier.

PE firms and management can then move right to determining the details of a pricing solution, calibrating, and accelerating the execution of that solution based on the existing road map.

Even portfolio companies that don’t have a pricing road map in their 100-day plans can create value with pricing during midtenure.

The timeline of designing a pricing solution varies greatly by the complexity and starting point of corporate capabilities, but it can typically take three to six months; another six to nine months of concentrated effort is generally necessary before the results of implementation are fully realized.

However, while full run-rate improvement can take between 18 and 24 months to achieve on an ongoing basis, we typically see quick pricing wins that boost earnings in the first or second quarter after focusing on pricing improvements.

With the cooperation and initiative of management teams, PE firms can improve the valuation of their companies at any point in the holding period by improving performance through pricing.

It is obvious that the pricing tools management and the investment team would prioritize this shift depending on where they are in the holding period.

What is less obvious is that shifting priorities means PE firms should revisit the traditional pricing tools for a tune-up throughout the life cycle of the asset.

These tune-ups will often result in new calls to action for marketing and sales teams.

Exit preparation: Demonstration of value

Starting 9 to 18 months before exit, the management and investment team should again review the pricing journey they have taken, documenting both the pricing tools they have used successfully and the opportunities that have not been fully utilized.

As with any value-creation tool—whether cost optimization, sales growth, or pricing improvements— articulating a successful value-creation story demonstrates the management team’s ability to deliver.

Management could even outline possible future value-creation opportunities for the new owners by studying remaining and new opportunities.

At an industrial machinery and components distributor, for instance, the management team conducted an exit diligence six months before starting the sale process.

As part of the diligence exercise, the team checked up on its pricing program (which had been ongoing for about two years) to see where it had made progress and where it was lagging behind.

The team also added some new initiatives to optimize margins within certain product categories (such as in-stock versus not-in-stock products), and they revised their 18- to 24-month pricing road map accordingly.

This revised road map, combined with the management team’s history of success in executing the initial pricing road map, gave potential new buyers confidence to bid aggressively for the company.

Pricing is undergoing a revolution fueled by advanced analytics, digital technologies, and the adoption of new models—such as dynamic pricing— across all industries.

This creates new opportunities and challenges, as well as an imperative to double down on pricing as the next frontier for value creation in PE. While PE has historically not focused on or confidently pursued pricing to date, now is the time to break away from outdated mind-sets.

Firms must embrace pricing as a primary way to create value. For despite perceived risks, substantial and sustainable value creation is often achievable.

And the earlier it starts, the better. Irrespective of where a portfolio company is in the deal cycle, there are tangible actions it can take to capture this value.

Hans van Eck-Casteels

O Professor Hans van Eck-Casteels, uma verdadeira autoridade no campo e com um currículo impressionante, já colaborou com empresas renomadas como IBM, van Eck Private Equity, Carlyle, KKR, Blackrock, France Telecom/Orange e AT Kearney.

Sua vasta experiência abrange otimização de custos, compras estratégicas, gerenciamento de riscos, estratégias de gerenciamento de fornecedores, bem como estratégias de TI e digitalização.

Além disso, o Professor possui certificações em Lean Six Sigma Green Belt, PMP, IA, Blockchain e Design Thinking, e é mestre em Economia pela prestigiosa Universidade de Oxford.